Six Senate Democrats last month sent a letter to the head of the Internal Revenue Service urging the federal tax agency to prohibit companies that make fuels from plastics and other petroleum products from qualifying for federal tax credits under the Inflation Reduction Act, President Biden’s landmark climate legislation.

The move was the latest in a string of bad developments for Fulcrum Bioenergy, the California firm that is seeking to turn Chicago-area trash and plastic waste into “sustainable” jet fuel at a Gary, Indiana, factory and construct a similar plant near Houston.

Shortly before the senators came out against tax credits for fuels made from dirty, high-energy processes the plastics industry calls “advanced recycling,” Fulcrum told the Indiana Finance Authority that it would delay financing its Gary project, called Centerpoint, with $500 million in bonds that the state authority had previously approved, a Finance Authority spokesperson confirmed.

Word of the delay came just days after Kansas City-based UMB Bank posted a notice on Oct. 17 that Fulcrum had defaulted on $289 million in bonds it used to finance the company’s first trash-to-fuel plant outside Reno, Nevada, called Sierra.

The bond default in Nevada immediately raised questions about Fulcrum’s other announced expansions, including a proposal for a waste-to-fuel plant in Baytown, Texas, a city along the Houston Ship Channel.

A Fulcrum official denied that the company’s decision to delay financing in Gary had anything to do with its default in Reno. “It is important to note that Fulcrum’s decision to not move forward with the Centerpoint bonds has no relation to the Sierra bonds,” said Rick Barazza, Fulcrum’s vice president.

But environmental advocates who have been fighting the Gary proposal locally and with state and federal regulators said it was hard not to suspect a connection.

“We think it means they are not producing what they proposed to produce in Nevada, and they are not making money,” said Dorreen Carey, cofounder and president of Gary Advocates for Responsible Development (GARD), a citizens group that has challenged the proposed plant’s air pollution permit from Indiana state regulators and filed Civil Rights Act complaint with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

“They are not able to pay their bond holders and that is never a good business sign,” she said.

The company has said it is also working to construct a plant about 25 miles east of Houston in Baytown, a city that’s also host to ExxonMobil’s sprawling, 3,400-acre Baytown Compex. Fulcrum has set a 2026 date to begin commercial production of fuel there at what it is calling its Trinity Fuels Plant with a goal of making 31 million gallons of “net-zero carbon jet fuel” each year.

Jennifer Hadayia, executive director of Air Alliance Houston, a clean-air and environmental justice advocacy group, said Fulcrum’s Baytown project is among three trash-to-jet-fuel plants proposed for the Houston area, which she said threaten to add health risks to a region already overburdened by pollution.

“This is not something we want in our community,” Hadayia said.

Barazza did not respond to a request for comment on the status of Fulcrum’s Baytown project.

The company is seeking to cash in on the airline industry’s desire to develop “sustainable aviation fuel,” often shortened to SAF, to lower greenhouse gas emissions from aviation. Still early in its development phase, SAF can be made with a variety of non-petroleum-based renewable feedstocks such as food scraps and yard waste, woody biomass, and fats, greases and oils, according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

But experts have said using a waste feedstock containing plastic complicates the fuel-making process in a couple of ways. First, plastic is made from a myriad of chemical mixtures, and gasification systems used to process it function the best with a consistent feedstock. And the more plastic in an SAF plant’s feedstock, the lesser the climate benefits because plastic is made from fossil fuels and emits greenhouse gases and other air pollutants when heated to high temperatures.

Making fuel out of plastic can also increase cancer risks to one in four over a lifetime of exposure to air pollution at production facilities, according to a February report based on a review of Environmental Protection Agency records by ProPublica and the Guardian. That’s 250,000 times the level deemed “acceptable” by the EPA.

The senators’ letter, dated Oct. 27, was sent to Daniel Werfelm, commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service. The signatories were Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.), Edward J. Markey (D-Mass.), Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), Cory Booker (D-N.J.), Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) and Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.).

They wrote that the language in the IRA is clear that petroleum products do not qualify for the SAF tax incentives because plastics are derived from petroleum products.

“Plastics are harmful from cradle to grave, including facilities that take plastic-based waste and refine it into chemicals used to make fuel, including aviation fuel,” the senators wrote. “These facilities emit toxic air pollution, and produce chemicals that raise significant concerns from the communities that are exposed. The petrochemical industry is increasing development of such facilities, and is poised to accelerate those efforts in the United States.”

They also wrote that it is “important” for the IRS to get the implementation of the IRA right, including SAF tax incentives. “Thanks to the clean energy investments made in the IRA, we have the opportunity to combat climate chaos through, in part, transitioning to sustainable fuels. However, we can’t get there if the petroleum industry is allowed to obfuscate their products and take advantage of the generous SAF tax incentives available in the IRA,” they wrote.

Chicago-based United Airlines has been among Fulcrum’s financial backers, and uses Oscar the Grouch from Sesame Street as the company’s “chief trash officer” as part of a public relations campaign for SAF.

A United spokesman declined to comment on Fulcrum’s financial situation or the senators’ letter. In a statement, the United spokesman said that Fulcrum was among several SAF companies that the airline has invested in or has purchase agreements with. On its website, United says SAF “is the fastest and most effective way we’re reducing lifecycle emissions across United’s fleet” and that “investing in and using more SAF across the entire airline industry will help fly us all toward a lower carbon future.”

In all, aviation contributes about 2 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. But when other impacts—including the heat-trapping effects of condensation trails planes paint across the sky—are factored in, aviation accounts for as much as 3.5 percent of warming caused by humans, according to research published last year in the journal Atmospheric Environment.

The Fulcrum plant in Nevada was among 11 chemical recycling plants in the United States highlighted by two environmental groups, Beyond Plastics and the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN), in an Oct. 31 report that described chemical recycling as a failed strategy for tackling a global problem of plastic pollution across its lifecycle. The Fulcrum plant in Nevada is a source of unwanted greenhouse gas emissions and pollutants that contribute to smog and toxic to human health, the group’s report concluded.

Fulcrum describes its technology as “part of the solution by providing the aviation industry with net-zero carbon, drop-in transportation fuel while reducing the amount of waste being disposed of in our landfills as we utilize this abundant, low-cost resource as feedstock.”

Last year, Inside Climate News was unable to verify Fulcrum’s somewhat less ambitious climate claims that the company would make fuel with an 80 percent reduction in greenhouse gases compared to traditional aviation fuel made from fossil fuels at its Nevada and Indiana plants. When asked for the studies the company said were the basis for those claims, Fulcrum declined to release them.

In Gary, company officials had assured residents that their Nevada plant was an example of what they could bring to the shores of Lake Michigan, said Carey, the local community activist. “The bond default notice in Nevada shows that GARD was right all along, and that the company and its technology “are not a good investment,” Carey said

The Gary project was announced in 2018 and construction was originally supposed to have begun in 2020, with completion within two years. The company’s website now predicts a 2026 completion date.

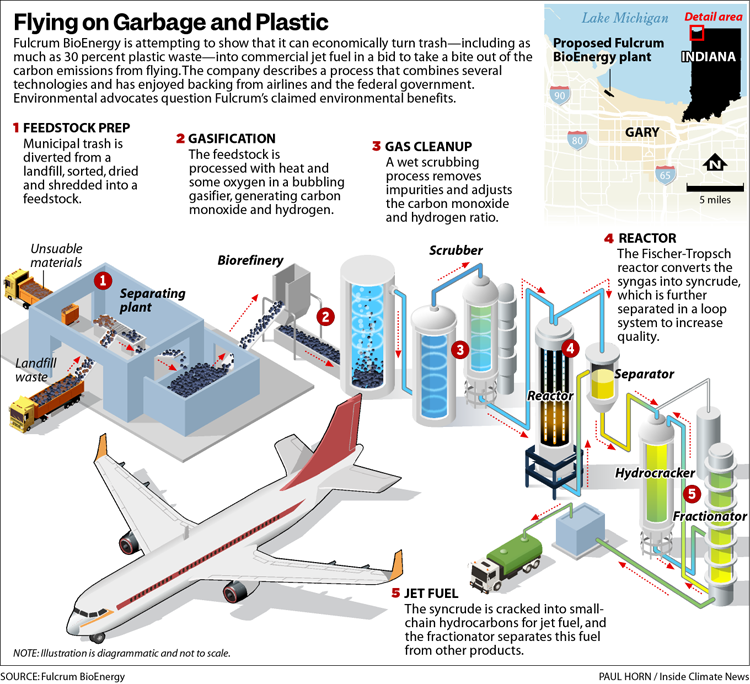

The plant is planned for a parcel of former industrial land where abandoned concrete silos rise from the remains of a cement factory that helped build the country’s interstate highway system. Fulcrum has proposed to construct a gasification plant and refinery to turn 700,000 tons of Chicago-area municipal solid waste—including as much as 30 percent plastic—into 31 million gallons of jet fuel annually.

Keep Environmental Journalism Alive

ICN provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going.

Donate NowThe company has been working to turn trash into aviation fuel for more than a decade. Its gasification process uses intense heat to turn the trash and plastic into a synthetic gas, before another process turns the gas into synthetic crude oil, which in turn is used to make jet fuel in an on-site refinery. While the plastics industry refers to gasification and a similar technology called pyrolysis as “advanced” recycling processes, the EPA regulates both as forms of incineration.

In addition to the bonds Fulcrum sold for the Nevada project, the company has also already sold $375 million in bonds for the Indiana plant, but has held the proceeds in an escrow account. Barazza said the Indiana bondholders would be repaid, with interest.

“Regarding the bonds for the Sierra project, Fulcrum is working closely with UMB and the Sierra bondholders to finalize a forbearance agreement to resolve the current matter with UMB,” Barazza said. “Fulcrum remains steadfast in its commitment to both the Centerpoint and Sierra projects and their respective bondholders.”

Last December, members of GARD filed a petition with the Indiana Office of Environmental Adjudication, charging that the air permit issued by the Indiana Department of Environmental Management for the Fulcrum Centerpoint plant violates Indiana law because it is based on inadequate information about the company’s feedstock and unsupported emissions calculations. On Nov. 13, GARD formally requested that a judge revoke the permit by filing for a summary judgment.

Carey also said GARD members are still waiting to hear how EPA will respond to a civil rights complaint it filed in 2022. The complaint related to the group’s assertion that the Fulcrum proposal in Gary would impose an oversized pollution on a community largely consisting of people of color with low incomes, less education and high unemployment rates.