A former Energy Department official is warning that the government may not be prepared to assess the effectiveness of new clean energy projects, pointing to what she called serious errors in a recent analysis of a major carbon capture and storage proposal in North Dakota.

The errors came in what’s called a life cycle assessment, or LCA, published by the department last month for a $1.4 billion effort that would remove and store millions of tons of carbon dioxide annually from the smokestacks of a coal plant.

The assessment is meant to help estimate and compare all the ways a project could increase or decrease pollution. In this case, however, it was riddled with mistakes, said Emily Grubert, an associate professor of sustainable energy policy at the University of Notre Dame and former deputy assistant secretary of carbon management at the Department of Energy, where she oversaw certain carbon capture programs until last year.

“The overall point that I came away with was that whoever did this LCA did not know what they were doing,” Grubert said.

The life cycle assessment, which was part of a larger draft environmental assessment, was performed not by department scientists but by a consultant hired by Minnkota Power Cooperative, the company that runs the coal plant, which is seeking funding for the carbon capture project. Grubert said it was equally concerning that the department did not catch the errors before publishing them last month for comment, a process that is meant to help the public understand potential impacts of development and weigh in on the proposal.

Grubert said she finds those deficiencies troubling because the federal government will have to rely increasingly on similar assessments as it prepares to help transform the nation’s energy system with a massive coming wave of subsidies. In the case of a new federal clean hydrogen tax credit, similar assessments could be used to determine how much money to provide to specific projects. Many environmental advocates have questioned the degree to which some of these clean hydrogen and carbon capture projects will actually help reduce emissions.

“Nobody caught these very, very basic problems,” Grubert said. “I have concerns for what that means when we get into the much more complex things that actually determine hundreds of billions to trillions of dollars of money being sent out.”

Some of the errors Grubert found were simple and obvious, like a calculation error which led to a determination that the power plant’s transmission systems release more climate-warming pollution than its smokestacks. Others were more systemic, she said, like improperly accounting for emissions from the carbon capture operations’ electricity consumption.

Surprisingly, Grubert said, the errors added up to make the carbon capture process’ climate footprint look far worse than it likely would be: It determined the operation would release more than three times more climate pollution than it would store underground, which is probably not true. Despite that finding, the environmental assessment recommended proceeding with an estimated $38.5 million in funding for the proposal, called Project Tundra.

“The analysis basically suggests this is not a good project for carbon management,” Grubert said, “and you are recommending to move ahead anyway.”

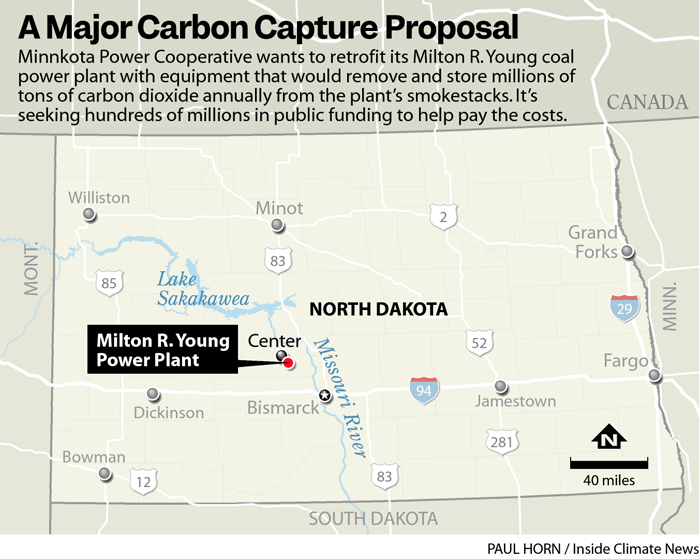

The draft assessment was completed as part of an Energy Department grant for Minnkota Power, which runs the Milton R. Young coal plant that would house the carbon capture operations. The company has also applied for a separate $350 million grant from the department to help fund Project Tundra.

An Energy Department spokesperson declined to comment on the details of the life cycle assessment, but noted in an emailed statement that the environmental assessment that it was part of was still in draft form and open for public comment through September 19. The statement added that the department “will continue to process comments, which includes analysis to determine the need, if any, for amendment to the final” environmental assessment. If any “material amendments” are made, the spokesperson said, the department would post a revised draft with an additional 30-day comment period.

Grubert submitted comments to the department last month outlining her concerns, concluding that the life cycle assessment “does not provide accurate and meaningful information to the public.”

Life cycle assessments are complex tools that aim to examine the full range of impacts from a given development. In the case of a carbon capture proposal, they could look at how a project might affect everything from coal mining to the electricity output of a given power plant, and how any of those changes might affect greenhouse gas emissions across not just the project in question but the larger energy system.

Ben Fladhammer, a Minnkota Power spokesperson, said in an email that the company “followed the appropriate guidelines and processes outlined by the Department of Energy and stands by the Life Cycle Analysis.” He did not dispute any of the errors Grubert identified, including the finding that the project would actually increase climate pollution. But he said that “[t]he Life Cycle Analysis and projected actual operations are two separate things. In terms of actual operations, Project Tundra will significantly reduce CO2 emissions.”

The concerns come as the federal government prepares to spend $12 billion in grants and loans to help build projects that would pull carbon dioxide from smokestack emissions and directly out of the air, part of the Biden administration’s larger goal to eliminate climate pollution nationwide by 2050. A newly expanded federal tax credit for carbon capture could provide even more federal support to companies that successfully store the greenhouse gas underground: Project Tundra alone stands to reap up to $4 billion over 12 years if it is completed and operates according to its design.

Many environmental advocates and scientists have warned that carbon capture and storage could prove to be an expensive distraction that will fail to meaningfully reduce climate pollution, particularly within the power sector, where wind and solar energy have become cheaper options for generating carbon-free electricity.

Carbon capture has largely failed to catch on in the power sector, though this week the company behind the nation’s only successful commercial operation announced it had restarted after being shut since 2020. That project, called Petra Nova, captured 3.8 million tons of carbon dioxide from 2017 through 2019 from a Texas coal plant, compared to a target of 4.6 million tons, according to a report by Energy Department, which provided $195 million in grants to the project. Petra Nova stores the captured carbon dioxide in an aging oil field, where it also helps increase production of the remaining crude.

John Thompson, the technology and markets director at the Clean Air Task Force, an environmental advocacy group, said carbon capture could play an important role in cutting pollution from hundreds of coal plants that will likely continue to operate for decades globally, with the largest number in China. Project Tundra, he said, could be a valuable demonstration of the technology and would meaningfully cut pollution from the Milton R. Young plant.

If the errors Grubert identified were indeed mistakes, Thompson said, they would be corrected in the public review process and would not affect the overall merits of the project or the findings of the larger environmental assessment, which determined that the project would reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Grubert and others dispute that the project would provide a meaningful net benefit to the climate, however, even if it were successful. One of the problems she identified in the life cycle assessment was its failure to compare the project to an alternative scenario in which the plant shuts down in the coming years. Because of the plummeting costs of wind and solar power, and improving technologies for battery storage, many energy experts argue that coal plants should be shut down early and replaced with renewable generation. In that scenario, of course, the Young plant’s emissions would fall to zero.

The World’s Largest

There are only two commercial coal plants globally that have been fitted with carbon capture equipment, and Project Tundra would be much larger, capturing up to 4 million metric tons of carbon dioxide per year, according to Minnkota Power. The effort is also farther along in its planning than many other proposals. In June, Minnkota Power said it had reached its final development stage and announced several partners, including Canadian pipeline firm TC Energy, which would be responsible for qualifying for the federal tax credit.

Project Tundra has won support from North Dakota’s governor and Congressional delegation. It was also promoted by Brad Crabtree, a North Dakota native who is currently the Energy Department’s assistant secretary for fossil energy and carbon management, before he joined the federal government. In his previous role Crabtree led a coalition of energy companies, unions and environmental organizations that advocated for more government support for carbon capture and storage.

Grubert said this high-level support raised concerns that decisions on Project Tundra grants could be made for political reasons, particularly in light of a December 2021 report by the Government Accountability Office about the Energy Department’s funding of carbon capture and storage projects. The report determined that the department’s process for selecting and negotiating agreements increased the risks that it would fund unsuccessful projects and that department leadership had directed staff to “not adhere to cost controls designed to limit its financial exposure on funding agreements for coal projects.” The result was that the department spent nearly $472 million on four projects that were not built.

In light of that report, Grubert said, “the fact that they’re doing this analysis that is, first of all, wrong, and second of all, shows that the project doesn’t have a greenhouse gas benefit, and nonetheless says ‘go for it,’… It’s not a great sign.”

Project Tundra has already received at least $27 million from the Energy Department and $250 million in state loans from North Dakota.

A department spokesperson said all funding decisions go through a merit review process and that Crabtree was not involved in deciding whether to award the grant that prompted the life cycle assessment.

Joe Smyth, a research and communications manager for the Energy and Policy Institute, a watchdog group that has been critical of carbon capture proposals, said Project Tundra is more likely to proceed than many other proposals, in part because of the support it has lined up.

“I think there’s a decent chance that the Department of Energy throws a lot of money at this,” Smyth said.

Smyth, Grubert and others have argued that the Milton R. Young plant is not a good candidate for carbon capture because it is about 50 years old, the average retirement age for the nation’s coal plants.

In May, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency proposed new climate rules that would require coal plants to either shut by 2032, switch partially to burn natural gas or, if they planned to operate beyond 2040, to capture at least 90 percent of their emissions.

Keep Environmental Journalism Alive

ICN provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going.

Donate NowIt’s unclear exactly what portion of the Young plant’s emissions Project Tundra would actually capture. While the draft environmental assessment says the project would capture 95 percent of the carbon dioxide emissions it processes, it wouldn’t necessarily process all of the plant’s exhaust. The Young plant has two units, and Fladhammer, the Minnkota spokesperson, said Project Tundra is designed to capture only 20 percent of the second unit’s exhaust, leaving the possibility that a significant volume of carbon dioxide could be vented straight to the atmosphere if that unit were running at high capacity. The operation’s total capacity to capture up to 4 million metric tons of CO2 per year is only about 74 percent of the plant’s average annual emissions.

Fladhammer said the company has continued to invest hundreds of millions in maintaining the Young plant and has no plans to shut it.

Thompson, with the Clean Air Task Force, argued that because of the company’s plans to keep operating the plant, it would be better to attach carbon capture equipment as soon as possible rather than allow its full emissions to escape into the atmosphere. According to the draft assessment, Minnkota Power plans to begin operating the carbon capture equipment in 2028.

For Grubert, the bigger concern is not what happens with Project Tundra but what the errors in its environmental assessment say about the government’s ability to manage what’s ahead.

“I’ve been worried for quite a while that we don’t necessarily have the capacity to see these things done well,” Grubert said, and the errors in the assessment reinforced that. Life cycle assessments will be central to ensuring that the government funds projects that actually cut climate pollution rather than wasting money on ones that don’t, yet they are extremely complex tools involving large volumes of data, many assumptions and deep knowledge of energy systems.

“If you are not super attentive to that, or heaven forbid if you’re actually trying to be malicious,” Grubert said, “it’s pretty easy to tweak a couple of the assumptions and basically make something say whatever you want it to.”